History of Japan

Legend attributes the creation of Japan to the sun goddess, from whom the emperors were descended. The first of them was Jimmu, supposed to have ascended the throne in 660 B.C. , a tradition that constituted official doctrine until 1945.

Recorded Japanese history begins in approximately A.D. 400, when the Yamato clan, eventually based in Kyoto, managed to gain control of other family groups in central and western Japan. Contact with Korea introduced Buddhism to Japan at about this time. Through the 700s Japan was much influenced by China, and the Yamato clan set up an imperial court similar to that of China. In the ensuing centuries, the authority of the imperial court was undermined as powerful gentry families vied for control.

At the same time, warrior clans were rising to prominence as a distinct class known as samurai. In 1192, the Minamoto clan set up a military government under their leader, Yoritomo. He was designated shogun (military dictator). For the following 700 years, shoguns from a succession of clans ruled in Japan, while the imperial court existed in relative obscurity.

First contact with the West came in about 1542, when a Portuguese ship off course arrived in Japanese waters. Portuguese traders, Jesuit missionaries, and Spanish, Dutch, and English traders followed. Suspicious of Christianity and of Portuguese support of a local Japanese revolt, the shoguns of the Tokugawa period (1603–1867) prohibited all trade with foreign countries; only a Dutch trading post at Nagasaki was permitted. Western attempts to renew trading relations failed until 1853, when Commodore Matthew Perry sailed an American fleet into Tokyo Bay. Trade with the West was forced upon Japan under terms less than favorable to the Japanese. Strife caused by these actions brought down the feudal world of the shoguns. In 1868, the emperor Meiji came to the throne, and the shogun system was abolished.

Japanese Culture

people

Japanese people Japan is famous for its supposed ethnic and social homogeneity, but there is much more to the story of the Japanese people than this popular myth. Today's vision of Japanese society includes minority groups that historically have been sidelined, such as the Ainu of Hokkaido and the Ryukyuans of Okinawa, as well as Koreans, Chinese, Brazilians and many more

apanese people appear at first glance to be one of the most socially and ethnically homogenous groups in the world.

It is reasonable to equate Japan's rapid post-war economic development to the 1990s with social solidarity and conformism. Despite labour shortages since the 1960s, authorities resisted officially sanctioning foreign workers until the 1980s, relying on increased mechanisation and an expanded female workforce instead (1).

Until recently, Japanese workers have associated themselves primarily with the company they work for - a businessman will introduce himself as "Nissan no Takahashi-san" (I am Nissan's Mr Takahashi). By extension, we might get the idea that a Japanese person subordinates the self to the objectives of society.

In 2008, however, long-serving Japanese politician Nariaki Nakayama resigned after declaring that Japan is "ethnically homogenous", showing that the old "one people, one race" idea has become politically incorrect.

Criticism of Mr Nakayama's statement focused on its disregard for the indigenous Ryukyukan people of southern Okinawa, and the Ainu people from the northern island of Hokkaido - colonised by the Japanese in the late nineteenth century.

In 1994 the first Ainu politician was elected to the Japanese Diet, suggesting that the Japanese are keen to officially recognise distinct ethnic groups in Japan.

Religion

Shinto, Buddhism and the Japanese belief system

Religion in Japan is a wonderful mish-mash of ideas from Shintoism and Buddhism. Unlike in the West, religion in Japan is rarely preached, nor is it a doctrine. Instead it is a moral code, a way of living, almost indistinguishable from Japanese social and cultural values.

Japanese religion is also a private, family affair. It is separate from the state; there are no religious prayers or symbols in a school graduation ceremony, for example. Religion is rarely discussed in every day life and the majority of Japanese do not worship regularly or claim to be religious.

However, most people turn to religious rituals in birth, marriage and death and take part in spiritual matsuri (or festivals) throughout the year.

Religion and the Emperor

Until World War Two, Japanese religion focused around the figure of the Emperor as a living God. Subjects saw themselves as part of a huge family of which all Japanese people were members.

The crushing war defeat however, shattered many people's beliefs, as the frail voice of the Emperor was broadcast to the nation renouncing his deity. The period since has seen a secularisation of Japanese society almost as dramatic as the economic miracle which saw Japan's post-war economy go into overdrive.

However, much of the ritual has survived the collapse of religious belief. Today, religion defines Japanese identity more than spirituality, and at helps strengthen family and community ties.

Shrines versus temples

As a general rule of thumb, shrines are Shinto and temples are Buddhist. Shrines can be identified by the huge entrance gate or torii, often painted vermillion red. However you'll often find both shrines and temple buildings in the same complex so it is sometimes difficult to identify and separate the two.

To appreciate a shrine, do as the Japanese do. Just inside the red torii gate you'll find a water fountain or trough. Here you must use a bamboo ladle to wash your hands and mouth to purify your spirit before entering.

Next, look for a long thick rope hanging from a bell in front of an altar. Here you may pray: first ring the bell, throw a coin before the altar as on offering (five yen coins are considered lucky), clap three times to summon the kami, then clasp your hands together to pray.

At a temple, you'll need to take your shoes off before entering the main building and kneeling on the tatami-mat floor before an altar or icon to pray.

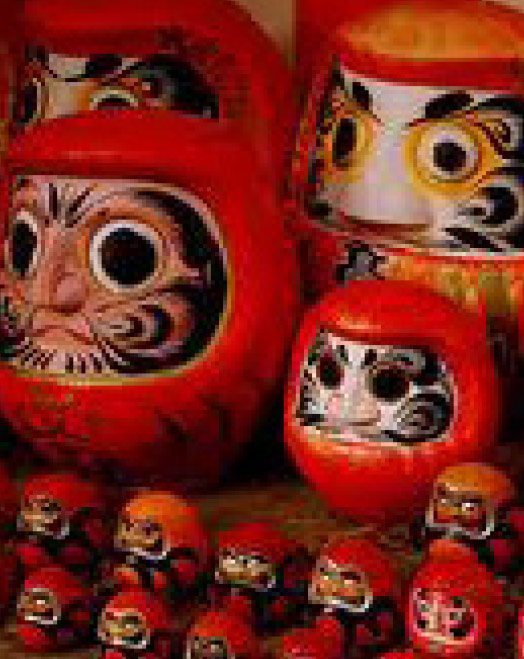

Lucky charms

Luck, fate and superstition are important to the Japanese. Many people buy small charms at temples or shrines, which are then attached to handbags, key chains, mobile phones or hung in cars to bring good luck. Different charms grant different luck, such as exam success or fertility.

Prayers are often written on votive tablets: wooden boards called ema that are hung in their hundreds around temple grounds. At famous temples such as Kyoto's Kiyomizu-dera, you'll see votive tablets written in a variety of languages.

A final way to learn your destiny is to take a fortune slip. Sometimes available in English, a fortune slip rates your future in different areas: success, money, love, marriage, travel and more. If your fortune is poor, tie your slip to a tree branch in the temple grounds; leaving the slip at the temple should improve your luck.

Religious ceremonies

The most important times of year in the Japanese calendar are New Year, celebrated from the 1st to the 3rd of January, and O-Bon, usually held around the 16th of August. At New Year the Japanese make trips to ancestral graves to pray for late relatives. The first shrine visit of the New Year is also important to secure luck for the year ahead.

At O-Bon it is believed that the spirits of the ancestors come down to earth to visit the living. Unlike Halloween, these spooky spirits are welcomed and the Japanese make visits to family graves.

Births are celebrated by family visits to shrines. The passing of childhood is commemorated at three key ages: three, five and seven, and small children are dressed in expensive kimono and taken to certain shrines such as Tokyo's Meiji Shrine. Coming of age is officially celebrated at 20. In early January, mass coming of age ceremonies (like graduations) are held in town halls followed by shrine visits by young people proudly dressed in bright kimono.

In Japan today, marriage ceremonies are a great clash of East meets West. A Japanese wedding may have several parts, including a Shinto ceremony in traditional dress at a shrine as well as a Western-style wedding reception in a hotel or restaurant. In the second part it is now popular for a bride to wear a wedding gown for a howaito wedingu (white wedding).

Funerals are overseen by Buddhist priests. 99% of Japanese are cremated and their ashes buried under a gravestone. To better understand Japanese funerals, InsideJapan Tours highly recommend the Oscar-winning film Okuribito, or Departures, about a concert cellist who goes back to his roots in Yamagata and retrains as an undertaker.

Japanese matsuri are festivals connected to shrines. In a tradition stretching back centuries matsuri parades and rituals relate to the cultivation of rice and the spiritual wellbeing of the local community.

Other religions

According to Article 20 of the Japanese constitution, Japan grants full religious freedom, allowing minority religions such as Christianity, Islam, Hinduism and Sikhism to be practiced. These religions account for roughly 5-10% of Japan's population. However, the spiritual vacuum left by the Emperor's renunciation was also rapidly filled by a plethora of new religions (shin shukyo) which sprung up across Japan.

Mainly concentrated in urban areas, these religions offered this-worldly benefits such as good health, wealth, and good fortune. Many had charismatic, Christ-like leaders who inspired a fanatical devotion in their followers. It is here that the roots of such famous "cults" as the "Aum cult of the divine truth", who perpetrated the Tokyo subway gas attack of 1995, can be found.

However, the vast majority of new religions are focused on peace and the attainment of happiness, although many Japanese who have no involvement appear suspicious of such organisations. Tax-dodging or money-laundering are, according to some, par for the course.

Some of the new religions, such as PL Kyoden (Public Liberty Kyoden) and Soka Gakkai, have, however, become very much a part of the establishment in Japan, and it seems their role in politics and business is not to be underestimated.

No comments:

Post a Comment